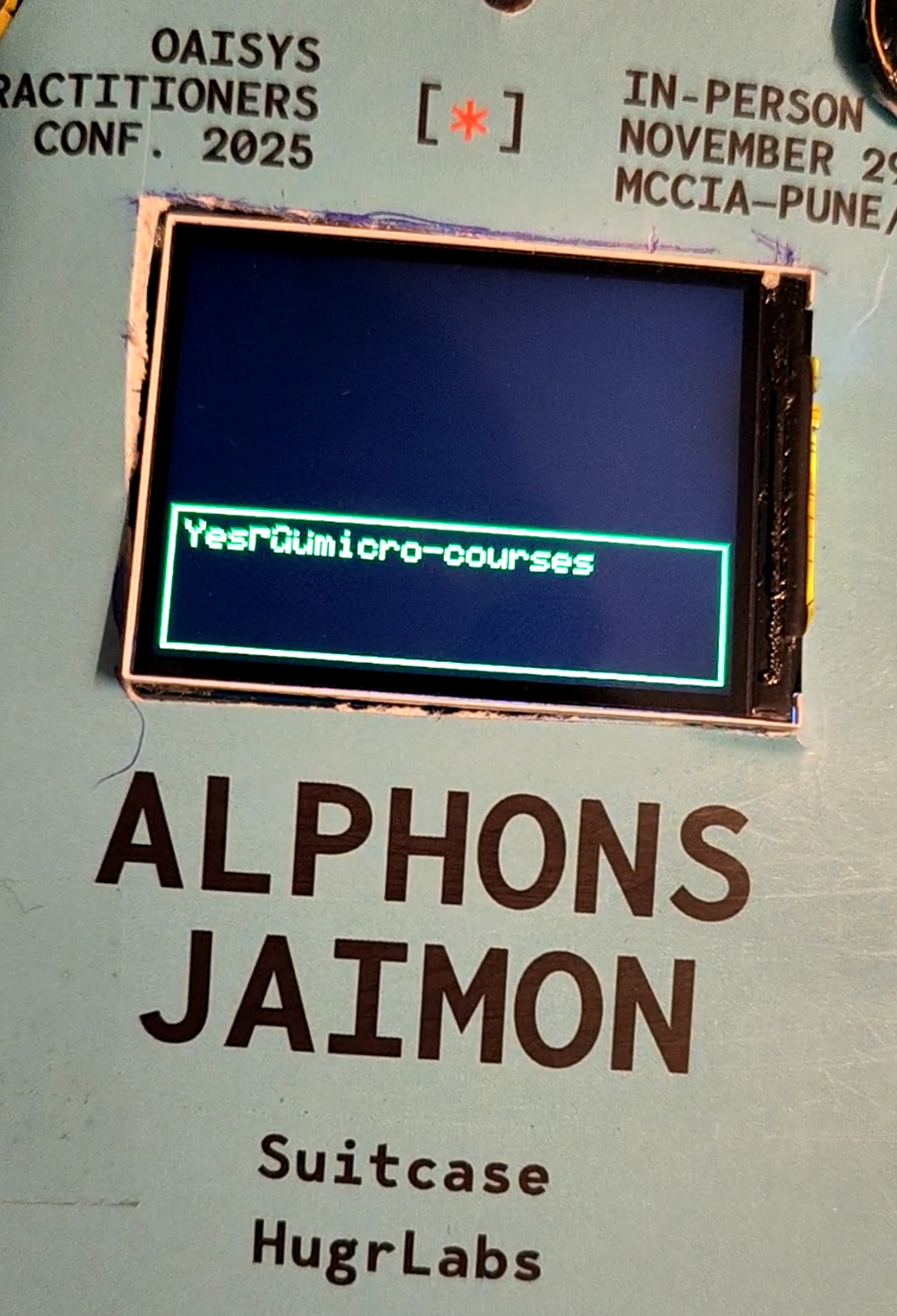

Fine-Tuned LLM with PIE Assembly, 6M, 5.56mb, 7tok/sec

- Embedded , Llm , Assembly

- December 3, 2025

If you’ve been following this series, you’ll know that back in our 2nd blog, we got a basic LLM running on the ESP32-S3. That was exciting - we had the Stories260K model generating children’s stories at 25-30 tokens per second using ESP-DSP’s float SIMD operations. It worked. It was cool. But it wasn’t making any sense.

This post is about what changed to make it meaningful. And fair warning: this is the flagship post of the series. We’re going deep into inline assembly, quantization theory, and training pipelines. Grab a BIG JUG of coffee.

In the 2nd blog, we had:

- Float32 inference using

dsps_dotprod_f32_aes3()from ESP-DSP - Dual-core parallelization with FreeRTOS

- Stories260K and Stories15M models

- ~25-30 tok/s for tiny models, ~0.25 tok/s for larger ones

Now we have:

- Int8 quantized weights (Q8_0 format)

- Custom PIE vector assembly for int8 dot products

- Fine-tuned model on 2K Q&A pairs about myself

- Three-phase training pipeline

- SAM robotic text-to-speech output

IT SOUNDS FUN NO?

The performance improvement? About 2-3x faster inference. But more importantly, we can now fit a 6MB model in PSRAM and have it actually do something useful - answer questions about me with genuine factual accuracy. So ESP-DSP’s SIMD is great for float operations, but the ESP32-S3 has a dedicated PIE (Processor Instruction Extension) vector unit with native int8 and int16 operations. If you’re using int8/16 weights, you’re leaving massive performance on the table by not using PIE.

Math and Assembly ahead

(I barely understand all this BS, but the pressure with not understanding enough is much better than being ignorant and dumb.)

int8 Quantization

Before we dive into assembly, let’s understand what Q8_0 quantization actually is. If you’re familiar with LLM quantization, feel free to skip ahead. If not, this is crucial context.

The Problem: Float32 (fp32/f32) weights are 4 bytes each. A 6M parameter model needs 24MB just for weights. The ESP32-S3 has 8MB of PSRAM. See the issue?

The Solution: Store weights as 8-bit integers with a floating-point scale factor per group of elements.

Here’s how Q8_0 works:

- Group Size: We process weights in groups of 64 elements (configurable, but 64 works well)

- Find Scale: For each group, find the maximum absolute value

- Compute Scale Factor:

scale = max_abs / 127.0 - Quantize:

q[i] = round(x[i] / scale)- each float becomes an int8 - Store: Save the 64 int8 values plus one float32 scale factor

The math simple:

Original: [0.5, -0.3, 0.8, ...] (64 floats = 256 bytes)

Quantized: [63, -38, 101, ...] + scale=0.00787 (64 bytes + 4 bytes = 68 bytes)

That’s 3.8x compression right there. And the best part? During inference, we can do integer dot products (fast!) and only multiply by the scale factors at the end (one multiply per group, not per element).

(I mentioned about literally cutting down the floats to int, thats something i did, it sort of works, but later when I tried to get the exact way karpathy quants worked claude corrected it to using scaling and all, so I apologize for half baked information back in the OAISYS Show n Tell event in Pune)

Here’s the quantization function from /home/alphons/project/OAISYS25/badge/local_llm_badge/src/ml/llm_core.cpp:

void quantize(QuantizedTensor *qx, float* x, int n) {

int num_groups = n / GS;

float Q_MAX = 127.0f;

for (int group = 0; group < num_groups; group++) {

float* gx = x + group * GS;

int8_t* gq = qx->q + group * GS;

// Find max absolute value using unrolled loop

float wmax = 0.0f;

for (int i = 0; i < GS; i += 4) {

float v0 = fabsf(gx[i]);

float v1 = fabsf(gx[i+1]);

float v2 = fabsf(gx[i+2]);

float v3 = fabsf(gx[i+3]);

if (v0 > wmax) wmax = v0;

if (v1 > wmax) wmax = v1;

if (v2 > wmax) wmax = v2;

if (v3 > wmax) wmax = v3;

}

float scale = wmax / Q_MAX;

qx->s[group] = scale;

// Quantize with reciprocal multiply (faster than division)

float inv_scale = (scale > 1e-10f) ? Q_MAX / wmax : 0.0f;

for (int i = 0; i < GS; i += 4) {

gq[i] = (int8_t)(gx[i] * inv_scale + 0.5f - (gx[i] < 0));

gq[i+1] = (int8_t)(gx[i+1] * inv_scale + 0.5f - (gx[i+1] < 0));

gq[i+2] = (int8_t)(gx[i+2] * inv_scale + 0.5f - (gx[i+2] < 0));

gq[i+3] = (int8_t)(gx[i+3] * inv_scale + 0.5f - (gx[i+3] < 0));

}

}

}

Notice the loop unrolling - we process 4 elements at a time. This isn’t for SIMD (we’re using scalar float ops here), it’s for instruction pipelining. The CPU can overlap the fabsf() calls and comparisons when we unroll like this. The + 0.5f - (gx[i] < 0) trick is rounding to nearest: add 0.5 for positive numbers, subtract 0.5 for negative (by subtracting 1 when negative). Clean and branchless. During export, we track the maximum quantization error per layer. For our 6M model, the worst-case error was about 0.002 - essentially imperceptible after the softmax in attention.

PIE Vector Unit Assembly

Okay, here’s where it gets fun. And by fun, I mean Claude figured out so many issues, I just watched in amazement thinking “damn these are issue?”. Haha yeah, things like you need to get your memory map right when writing assembly inside your cpp code. Like thats crazy thinking about writing ASM inside your CPP. (I never thought I had to do this after my college, anyways here we are…)

The ESP32-S3 has a PIE (Processor Instruction Extension) vector unit. This is NOT the same as the AES3 instructions that ESP-DSP uses for float SIMD. PIE is a separate coprocessor with dedicated instructions for int8/int16 vector operations.

Let me break down what we have to work with:

PIE Registers:

q0-q7: 128-bit vector registers. Each can hold 16 x int8, 8 x int16, or 4 x int32accx: 40-bit accumulator. This is crucial - it prevents overflow during long accumulations

Key Instructions We Use:

ee.vld.128.ip q0, %[ptr], 16: Load 128 bits (16 bytes) from memory, auto-increment pointer by 16ee.vmulas.s8.accx q0, q1: Multiply 16 signed int8 pairs and accumulate sum to accxwur.accx_0 %[val]/wur.accx_1 %[val]: Write to low/high parts of accumulatorrur.accx_0 %[result]: Read low 32 bits of accumulatorloopnez %[count], label: Hardware zero-overhead loop

PIE in Matrix Multiplication

The dot product is nice, but matrix multiplication is where we spend most of our time. Every attention layer, every FFN layer, every projection - it’s all matmuls.

Here’s how we use our PIE dot product in the quantized matrix multiplication:

void matmul_q8(float* xout, QuantizedTensor* x, QuantizedTensor* w, int n, int d) {

for (int i = 0; i < d; i++) {

float val = 0.0f;

int in = i * n;

// Process each quantization group with SIMD

for (int j = 0; j <= n - GS; j += GS) {

// SIMD dot product for this group (GS elements)

int32_t ival = dotprod_s8_simd(x->q + j, w->q + in + j, GS);

// Scale by quantization scales (float32)

val += (float)ival * w->s[(in + j) / GS] * x->s[j / GS];

}

xout[i] = val;

}

}

The structure is:

- For each output dimension (d rows)

- For each quantization group (GS elements at a time)

- Do integer dot product with SIMD

- Multiply by the two scale factors (one from weights, one from activations)

- Accumulate to float output

The key insight: we only do 2 float multiplies per group (one multiply to combine scales, one to accumulate). The expensive dot product with 64 multiply-adds happens in integer SIMD land.

For a typical layer with n=224, d=224:

- 224 * 224 = 50,176 total output elements per matmul

- Each needs 224/64 = 3.5 (rounded to 4) groups

- 4 SIMD dot products per output element

- 50,176 * 4 = 200,704 SIMD operations

- Each SIMD op processes 64/16 = 4 loop iterations

- Each iteration does 16 MACs

That’s 200,704 * 4 * 16 = 12.8 million multiply-accumulates per matmul. And our model has MANY matmuls per token.

Memory Alignment: Notice in the allocation code we use heap_caps_aligned_alloc(16, ...) for the quantized buffers. PIE’s vector loads require 16-byte alignment or you get undefined behavior (usually a crash with a cryptic backtrace).

Other SIMD Optimizations

PIE assembly handles our int8 matmuls, but we still have float operations throughout the model. For those, we use ESP-DSP’s AES3 SIMD instructions.

RMSNorm with SIMD:

void rmsnorm(float* o, float* x, float* weight, int size) {

// Sum of squares using SIMD dot product

float ss = 0.0f;

dsps_dotprod_f32_aes3(x, x, &ss, size);

// Normalization factor

ss = 1.0f / sqrtf(ss / size + 1e-5f);

// Scale x by ss, then multiply by weight

dsps_mulc_f32_ae32(x, o, size, ss, 1, 1); // o = x * ss

dsps_mul_f32_ae32(o, weight, o, size, 1, 1, 1); // o = o * weight

}

The idea here is that dsps_dotprod_f32_aes3 computes x dot x (sum of squares) in one SIMD call. Then we use vectorized scalar multiply and element-wise multiply for the normalization.

Softmax with Numerical Stability:

void softmax(float* x, int size) {

// Find max (no SIMD equivalent that's faster for small arrays)

float max_val = x[0];

for (int i = 1; i < size; i++) {

if (x[i] > max_val) max_val = x[i];

}

// Exp and sum (expf() is the bottleneck, can't SIMD this)

float sum = 0.0f;

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

x[i] = expf(x[i] - max_val);

sum += x[i];

}

// Vectorized division using SIMD multiply by inverse

float inv_sum = 1.0f / sum;

dsps_mulc_f32_ae32(x, x, size, inv_sum, 1, 1);

}

The x[i] - max_val before exp is the numerical stability trick - without it, large values would overflow expf(). The final normalization uses SIMD multiply by reciprocal instead of division (multiply is faster).

SwiGLU Activation with Unrolling:

for (int i = 0; i < hidden_dim; i += 4) {

// Unrolled for better pipelining

float v0 = s->hb[i], v1 = s->hb[i+1], v2 = s->hb[i+2], v3 = s->hb[i+3];

// SiLU: x * sigmoid(x)

v0 *= 1.0f / (1.0f + expf(-v0));

v1 *= 1.0f / (1.0f + expf(-v1));

v2 *= 1.0f / (1.0f + expf(-v2));

v3 *= 1.0f / (1.0f + expf(-v3));

// Gate multiply

s->hb[i] = v0 * s->hb2[i];

s->hb[i+1] = v1 * s->hb2[i+1];

s->hb[i+2] = v2 * s->hb2[i+2];

s->hb[i+3] = v3 * s->hb2[i+3];

}

This is the SwiGLU activation (SiLU gated linear unit). We can’t easily SIMD the sigmoid computation, but we can unroll to help the instruction pipeline overlap the independent calculations.

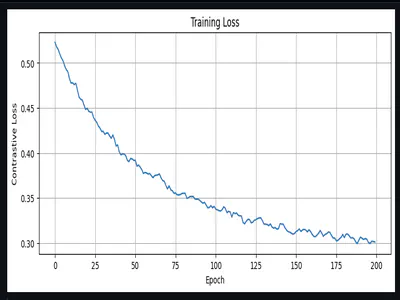

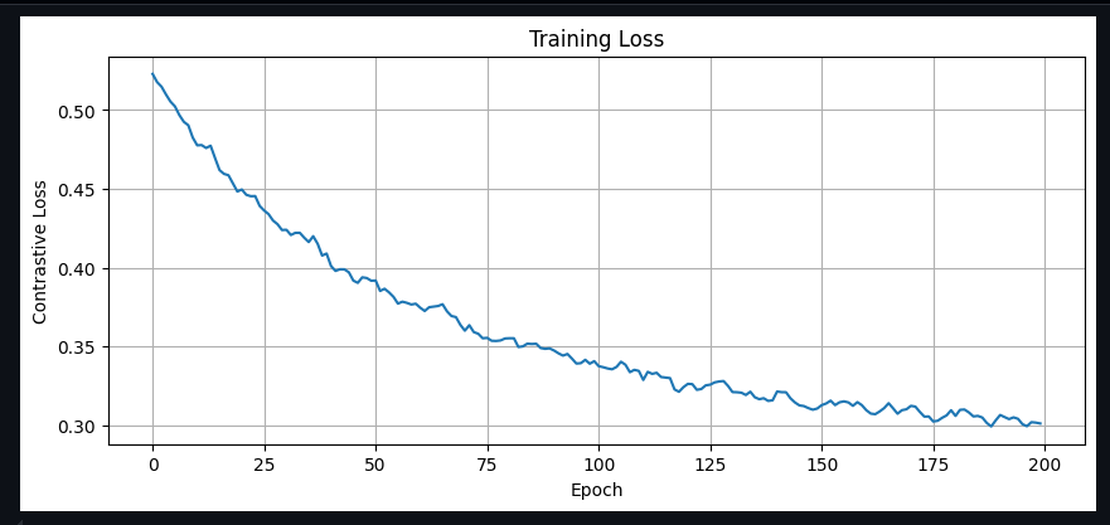

Three-Phase Training Pipeline

Fast inference is useless if the model generates garbage. Our model needed to answer questions about a specific person accurately. This required a careful training pipeline.

Why Three Phases?

The intuition comes from transfer learning: teach the model to speak English first, then teach it facts, then teach it the Q&A format. Each phase builds on the previous. The training notebook lives at /home/alphons/project/OAISYS25/badge/workbench/tests/llm_qa_scaled_training/llm_qa_scaled_training.ipynb.

Phase 1: TinyStories (Language Structure)

Dataset: 200,000 children’s stories from the TinyStories dataset Steps: 20,000 Final Loss: 1.5507 Learning Rate: 3e-4 (Higher LR for learning general language patterns. We can afford to move weights around.)

"Once upon a time, there was a little girl named Lucy. She had a big,

red balloon. One day, she went to the park with her mom..."

The model learns grammar, sentence structure, coherent narrative flow. It doesn’t know anything about our target person yet - it’s just learning how language works.

This is crucial. If you skip this phase and go straight to Q&A training, the model memorizes the Q&A pairs but produces incoherent responses when asked novel questions.

Phase 2: Profile Grounding (Factual Knowledge)

Dataset: AI generated prose paragraphs about the person + synthetic Q&A pairs Steps: 10,000 Final Loss: 0.0133 (very low!) Learning Rate: 1e-4 (Medium LR for adding factual knowledge. Don’t destroy language skills.)

Here’s where it gets interesting. We used some random GenAI models to:

- Extract prose paragraphs from the profile (50+ different phrasings)

- Generate 242 synthetic Q&A pairs across 7 categories

Categories: contact info, current work, skills & expertise, work history, education, projects, personal interests.

Sample prose:

"Alphons Jaimon embodies the spirit of 'Limitless Ideation,' channeling

his passion from innovation through development to actualization in the

tech realm. Currently serving as a GenAI Engineer at Etherwise since

August 2025, he architects and builds full GenAI applications..."

Sample synthetic Q&A:

Q: What is Alphons email address

A: [email protected]

Q: Does Alphons know Python

A: Yes he is proficient in Python

The model now knows facts about the person, phrased in many different ways.

Phase 3: Q&A Memorization (Task-Specific)

Dataset: 2,008 human-written Q&A pairs, repeated 50 times = 100,400 samples Steps: 12,000 Final Loss: 0.2378 Learning Rate: 5e-5 (Low LR for fine-grained memorization. Preserve everything, just add Q&A skills)

This is pure memorization. We have 2,008 specific questions we want the model to answer correctly. By repeating them multiple times and shuffling, we hammer these into the model’s weights.

Sample from the dataset:

1,What is Alphons email address,[email protected]

2,What is his phone number,+91-8237842347

3,When was Alphons born,August 2001

4,Where does he live,Maharashtra India

5,What languages does Alphons know,English Hindi Marathi Malayalam

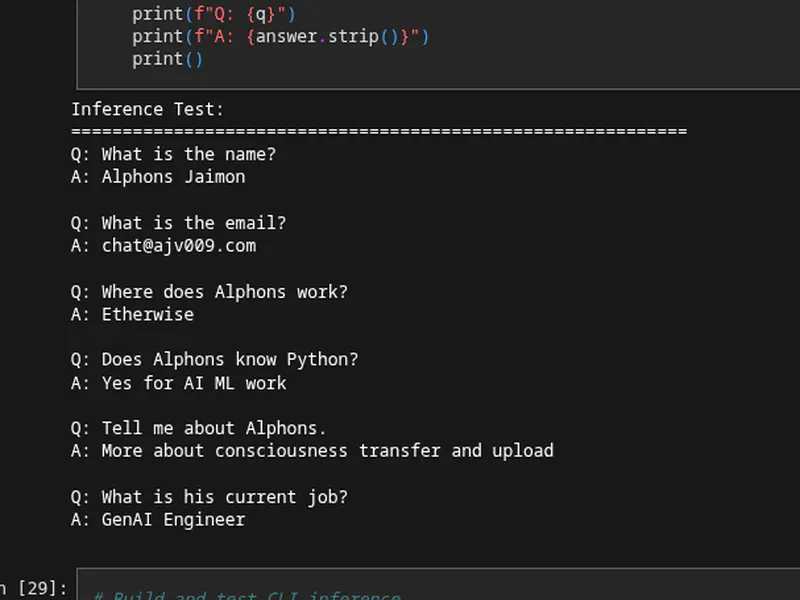

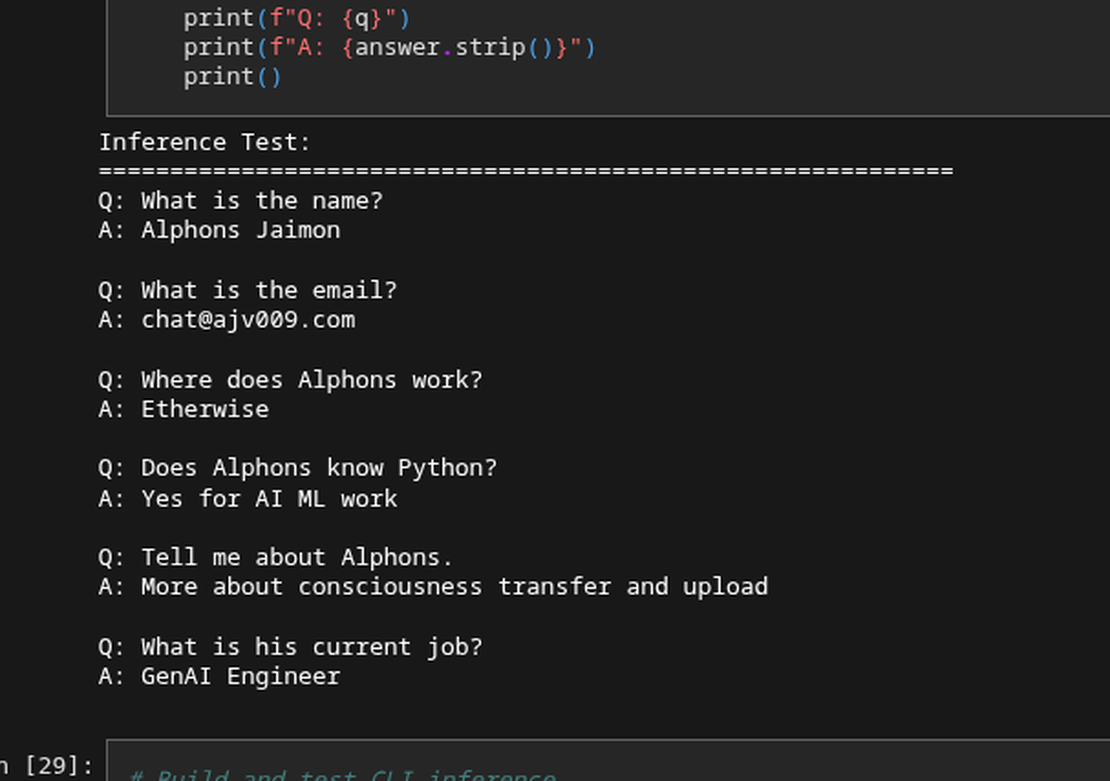

Training Results

The final 6M model achieves:

- Stories loss: 1.55 (can still write coherent sentences)

- Profile loss: 0.01 (knows the facts cold)

- Q&A loss: 0.24 (good at the Q&A task)

Test inference:

Q: What is the name?

A: Alphons Jaimon

Q: What is the email?

A: [email protected]

Q: Where does Alphons work?

A: Etherwise

Q: Does Alphons know Python?

A: Yes for AI ML work

It works! The model gives accurate, concise answers. Scoff me all you want, yeah I made it memorize facts about it. I mean it was going to go into my conference badge and was supposed to be tiny at less than 6MB to run, what was I supposed to do.

Now not everyone needs a 6M parameter model. We trained several sizes:

| Size | Parameters | Int8 Size | Memory Footprint | Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1M | 1,070,000 | 1.07 MB | ~1.5 MB | Fast, but limited |

| 3M | 2,820,000 | 2.82 MB | ~3.5 MB | Good balance |

| 6M | 5,566,176 | 5.98 MB | ~6.5 MB | Best quality |

The architecture scales by adjusting:

dim: Embedding dimension (128 -> 224)hidden_dim: FFN hidden size (512 -> 896)n_layers: Transformer layers (4 -> 8)

All models use 8 attention heads with grouped-query attention (4 KV heads) to reduce memory.

Vocabulary Size: We train custom SentencePiece tokenizers with 512 or 1024 tokens. Smaller vocab = more tokens per response, but better handling of rare words. 1024 tokens works well for our Q&A domain.

For the badge, we use the 6M model because: It fits in PSRAM (barely - about 6.5MB total with buffers) Quality matters more than speed for Q&A (we only generate once per interaction) The user is waiting anyway while we load the model

SAM TTS Integration

With the LLM generating text responses, we need the badge to actually speak. Enter SAM - Software Automatic Mouth. Its is a speech synthesizer from 1982, originally for the Commodore 64. It’s wonderfully robotic, requires no neural networks, and fits in about 10KB of code. Perfect for a conference badge. We use the ESP32-SAM library by pschatzmann. The integration is straightforward but requires a custom I2S output adapter since SAM’s default output doesn’t match our MAX98357A setup.

From /home/alphons/project/OAISYS25/badge/local_llm_badge/src/tts/robot_tts.cpp:

class SAMI2SOutput : public SAMOutputBase {

public:

void open() override {

i2s_config_t i2s_config = {

.mode = (i2s_mode_t)(I2S_MODE_MASTER | I2S_MODE_TX),

.sample_rate = SAMOutputBase::sampleRate(), // 22050 Hz

.bits_per_sample = I2S_BITS_PER_SAMPLE_16BIT,

.channel_format = I2S_CHANNEL_FMT_RIGHT_LEFT,

.communication_format = I2S_COMM_FORMAT_STAND_I2S,

.intr_alloc_flags = ESP_INTR_FLAG_LEVEL1,

.dma_buf_count = 8,

.dma_buf_len = 256,

.use_apll = false,

.tx_desc_auto_clear = true,

};

i2s_driver_install(_port, &i2s_config, 0, NULL);

i2s_set_pin(_port, &pin_config);

}

bool write(byte* buffer, int bytes_count) override {

size_t bytes_written;

i2s_write(_port, buffer, bytes_count, &bytes_written, portMAX_DELAY);

return true;

}

};

SAM outputs at 22050 Hz, which is its native sample rate. We configure I2S to match, avoiding any resampling.

Voice Configuration:

SAM has four parameters that shape the voice:

- Speed: How fast it speaks (higher = faster)

- Pitch: Fundamental frequency (higher = squeakier)

- Throat: Resonance cavity size (higher = more hollow)

- Mouth: Lip/mouth shape (affects vowel sounds)

For maximum robotic effect:

void setVoice(Voice voice) {

switch (voice) {

case ROBOT:

_sam->setSpeed(100); // Slower for dramatic effect

_sam->setPitch(50); // Lower pitch

_sam->setThroat(200); // Harsh throat

_sam->setMouth(200); // Wide mouth resonance

break;

}

}

The result is a classic 1980s computer voice - exactly what you want from a conference badge. It’s deliberately inhuman, which makes it charming rather than unsettling (looking at you, uncanny valley TTS). I’ll be honest: I didn’t spend much time tuning SAM. It’s a mature, well-documented library that just works. The whole TTS integration was maybe like 2-3 prompts including debugging I2S pin conflicts.

Performance Results

Let’s talk numbers.

Inference Speed:

- Before (float32, ESP-DSP SIMD): ~2-4 tok/s for 6M model

- After (int8, PIE assembly): ~7 tok/s

Memory Usage (6M model):

- Raw model weights: ~6 MB

- Token embeddings (dequantized): ~0.4 MB

- KV cache: ~0.5 MB

- Activation buffers: ~0.2 MB

- Total: ~7 MB (fits in 8 MB PSRAM with room to spare)

Lessons Learned

This was the most technically challenging part of the badge project. Some hard-won lessons:

1. Assembly is hard but worth it for hot loops I still don’t get every line of it as is. Register clobbering, alignment issues, accumulator overflow - every bug was subtle and hard to diagnose, but even Claude code doing guess works, now thats what I call absolutely beautiful AI assistance. And the payoff was real. For the inner loop of matmul (which we execute millions of times per token), 2x speedup is huge. Don’t optimize everything with assembly - just the hot paths.

2. Quantization quality depends on training data We initially tried to take a pre-trained model and quantize it. The results were bad - the model would hallucinate, forget facts, and generally misbehave. Training from scratch with quantization-aware training would be better, but we compromised: train in float32, then quantize carefully. The three-phase approach helps because each phase can recover from any drift introduced by quantization.

3. Three-phase training is more stable than end-to-end Phased training with decreasing learning rates is slower but much more predictable. Each phase has clear success criteria (loss thresholds), and you can checkpoint between phases for recovery.

4. Memory alignment is not optional The ESP32-S3 PIE instructions REQUIRE 16-byte aligned pointers. The code will crash with no helpful error message if you pass unaligned pointers. Always use heap_caps_aligned_alloc(16, size, MALLOC_CAP_SPIRAM) for anything that touches PIE. Don’t trust regular malloc, even if the addresses happen to be aligned on your test runs.

5. Claude Code is genuinely helpful for assembly I used Claude extensively for this work. It helped me understand PIE instruction semantics, suggested the loopnez zero-overhead loop, and caught several register allocation bugs. I verified everything on hardware, but yeah it was fun trying to do something I normally wouldn’t have been able to, or maybe it would have taken me weeks to get this up properly (well that would have paid off as well, I would have ended up being a genius by then.)

What’s Next

With LLM inference and TTS working, the badge can now:

- Detect a wake word (Blog 3/4)

- Record audio and compute embeddings

- Search for matching intents

- Generate a response with the LLM

- Speak the response with SAM

The next post (Blog 6) will cover the integration of all these components and the final polish - sleep modes, error handling, and the complete user experience.

If you’re building something similar and get stuck on PIE assembly, (DON’T) feel free to reach out. It’s a niche topic and I’m (NOT) happy to help. (at times its super confusing on me already) Until next time - keep building weird things. (Use Claude Code to debug and understand stuff. And yeah am kidding, feel free to reach out if you needed to understand some specific aspect of the project.)