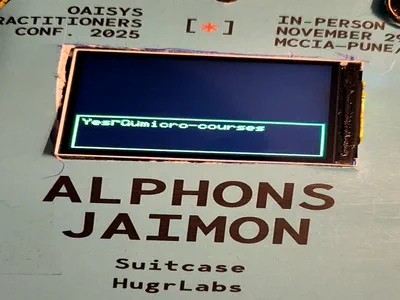

Video Badge using ESP32-S3

- Hardware , Embedded systems

- November 9, 2025

A quick backstory

So QED42, my previous company is hosting an AI conference soon in last week of November 2025, and hey I just thought it would be really cool if I can the event logo animated on a badge that I will put inside the lanyard. So I first got the video animated using Google Veo 3.1 on Weavy.ai which Figma recently acquired.

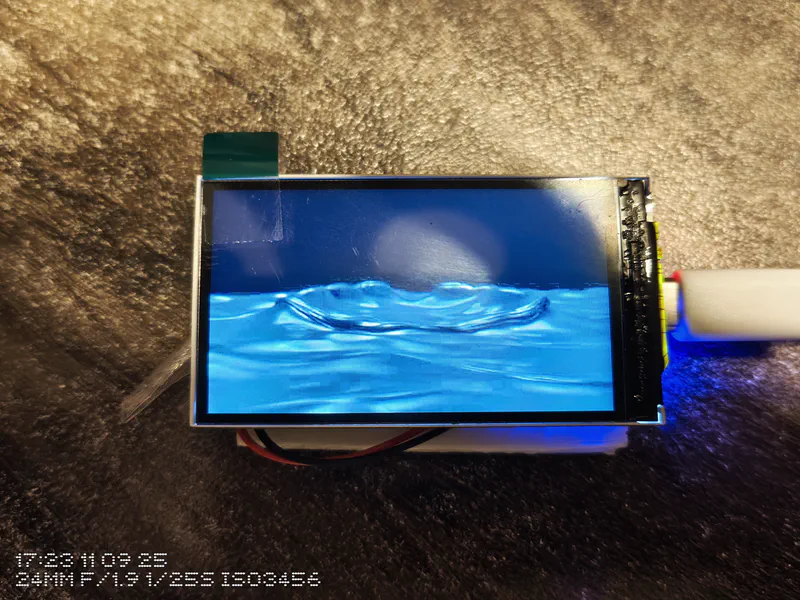

Since I was a bit cash tight I had to think of a very cheap and way way to do this. Randomly explored my regular site Robu.in and found that a lot of ESP32 boards came with LCD displays, that too as small as 1.3 inches to 2.4 inches. I thought why not use one of those boards to display the video. After filtering based on cost and an ideal size and features I finally settled on the Waveshare ESP32-S3-LCD-2 board which costed me around 1.5K INR or 17 USD at the time of purchase. (Nov 2025)

Spoiler: It’s pretty easy to hack around and awesome to just look at.

I wanted to build something that could:

- Play a video file in an infinite loop

- Store the video in flash memory (no SD card, because I had trouble with getting older SD card up and running, it was too much hacky work for a simple project)

- Automatically rotate the display based on device orientation

- Respond to button presses (pause/play, power management)

- And finally run smoothly without stuttering!

Think of it like a digital photo frame, but cooler because it’s a video badge that knows which way is up. Hehe

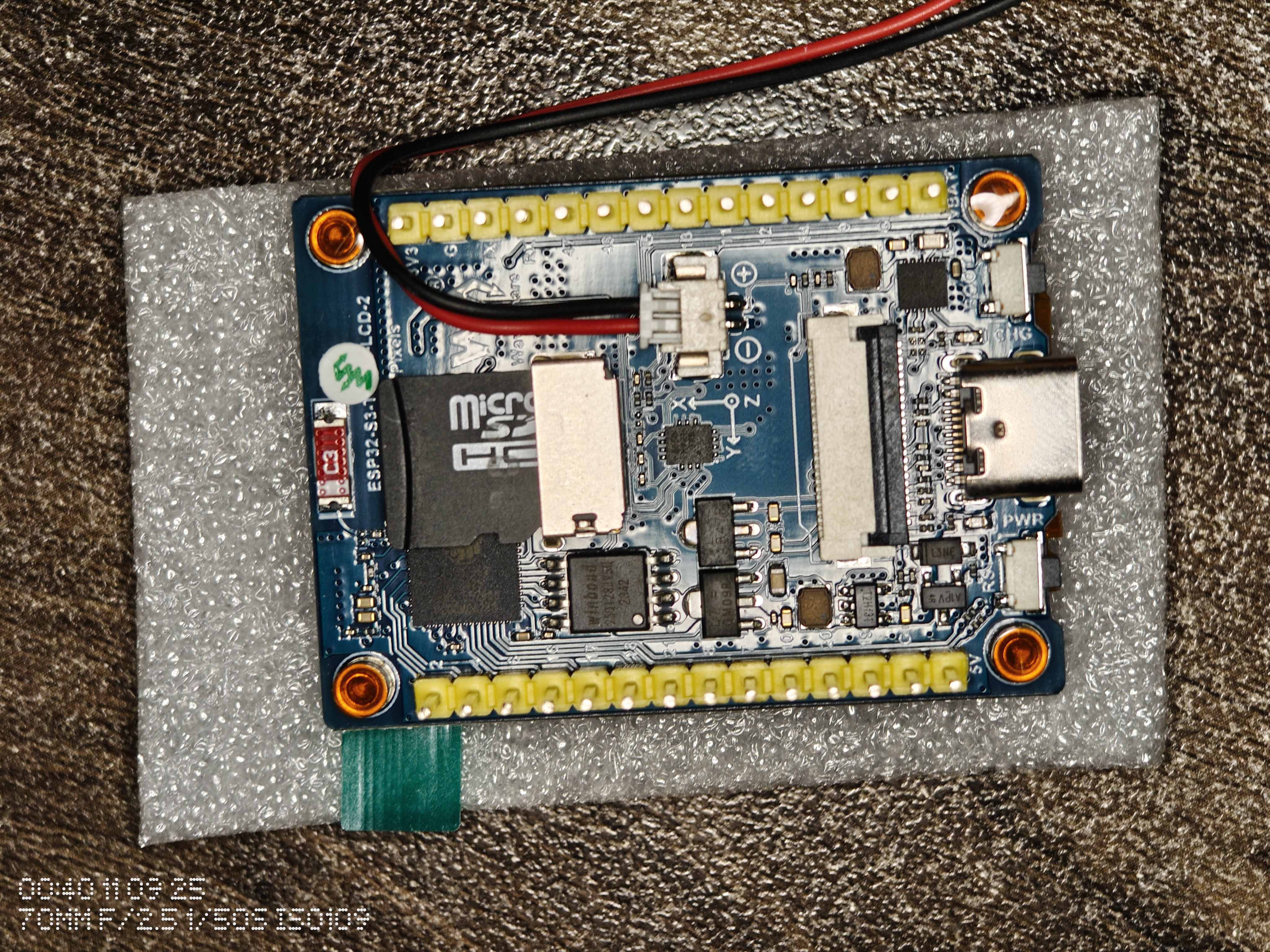

The Hardware: ESP32-S3-LCD-2

The board I’m working with is the ESP32-S3-LCD-2, which is basically an all-in-one solution for display projects. Here’s what makes it interesting:

- ESP32-S3R8 chip: Dual-core Xtensa LX7 @ 240MHz

- Memory: 512KB SRAM + 8MB PSRAM (this PSRAM is crucial for video buffering)

- Display: 2" ST7789T3 LCD with 240×320 resolution

- IMU: QMI8658 6-axis sensor (accelerometer + gyroscope)

- Storage: 16MB Flash memory + SD Card Slot

- Connectivity: USB-C for programming and power

- Buttons: BOOT button (GPIO 0) for user input

- Battery: 3.7V lithium battery charge/discharge JST 1.25mm header

What’s great about this board is that everything is already wired up. No breadboard maze, no jumper wires, no wondering if you got the SPI pins right. Just plug it in and start coding.

Read more about the board here:

Video Component

Why MJPEG?

First question: What video format should we use? The options aren’t great for microcontrollers:

- H.264/MP4: Too complex, requires dedicated hardware decoder

- Raw RGB frames: 240 × 320 × 2 bytes × 30fps = Way too much data

- GIF: Limited colors, larger files than you’d expect

- MJPEG: Just a series of JPEG images back-to-back

MJPEG (Motion JPEG) turned out to be perfect for this use case. It’s essentially just JPEG images played one after another, which means:

- We can decode one frame at a time (low memory overhead)

- JPEG compression is efficient (~90% size reduction)

- No complex inter-frame dependencies

- Easy to seek and loop

The tradeoff is file size compared to modern codecs like H.264, but for a 3-second loop stored in flash? MJPEG is ideal.

Converting Video with FFmpeg

Getting video into MJPEG format is straightforward with FFmpeg. Here’s what I’m doing:

ffmpeg -i input.mp4 -vf "scale=320:240" -q:v 15 -r 10 output.mjpeg

Let’s break this down:

- -i input.mp4: Input video file

- -vf “scale=320:240”: Resize to 320×240 to match the display resolution

- -q:v 15: JPEG quality (2-31 scale, lower is better quality, 15 is a good balance)

- -r 10: Frame rate of 10 frames per second (smooth enough while keeping file size manageable)

- output.mjpeg: Output file in MJPEG format

The result is a 1.2MB file for about 3 seconds of video. Small enough to fit comfortably in flash with room to spare.

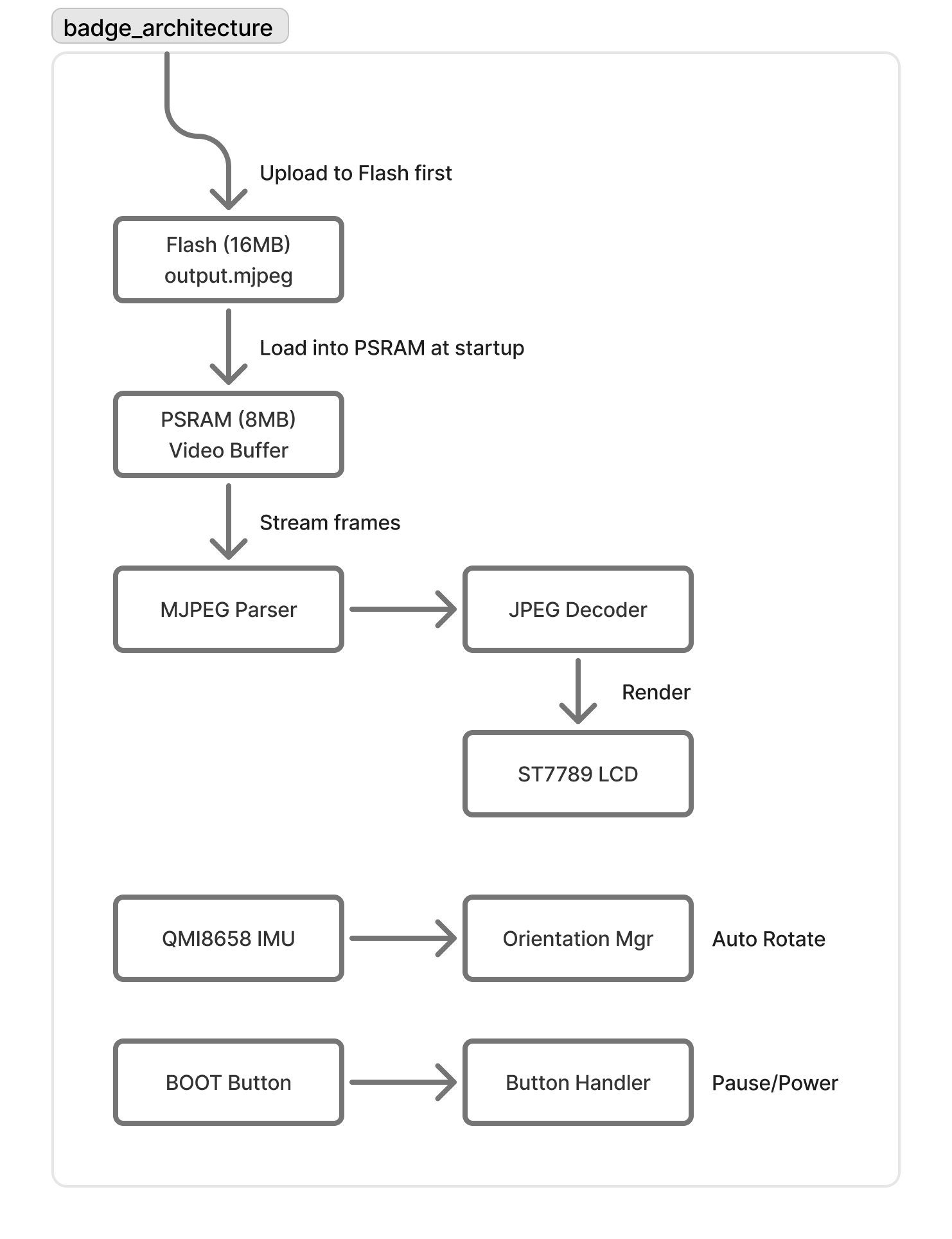

The Architecture: How It All Fits Together

Here’s the high-level flow:

The key insight: Load the entire video into PSRAM (external RAM) at startup, then stream from there. PSRAM is slower than internal SRAM, but it’s perfect for bulk storage like this.

Memory & Streaming Strategy

PSRAM vs SRAM

The ESP32-S3 has two types of memory:

- SRAM (512KB): Fast, but limited

- PSRAM (8MB): Slower, but abundant

Here’s how I’m using them:

// Load entire video into PSRAM (external RAM)

size_t fileSize = videoFile.size();

videoBuf = (uint8_t*)ps_malloc(fileSize); // ps_malloc = PSRAM allocation

videoFile.read(videoBuf, fileSize);

// Decode buffer in SRAM (faster for active processing)

decodeBuf = (uint8_t*)malloc(320 * 240 / 2); // malloc = SRAM allocation

Why this works:

- Video buffer (1.2MB) → PSRAM (plenty of space)

- Decode buffer (38KB) → SRAM (speed matters here)

- Working memory → SRAM (everything else)

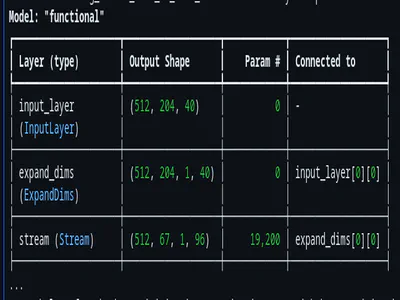

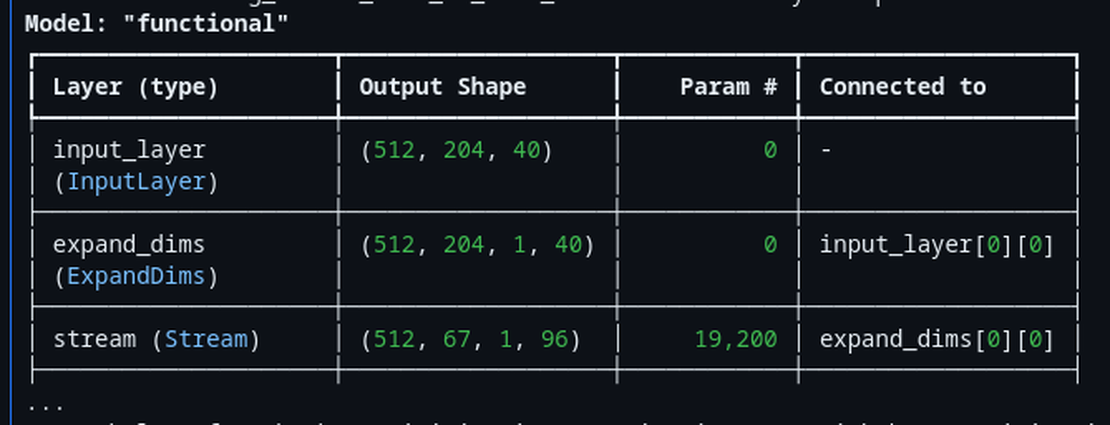

The MemoryStream Class: Streaming from PSRAM

To make the video loop infinitely, I created a simple MemoryStream class that implements Arduino’s Stream interface:

class MemoryStream : public Stream {

uint8_t *buf;

size_t sz, pos;

public:

MemoryStream(uint8_t *b, size_t s) : buf(b), sz(s), pos(0) {}

int available() override { return sz - pos; }

int read() override {

return (pos < sz) ? buf[pos++] : -1;

}

void reset() { pos = 0; } // Loop back to start!

// ... other Stream interface methods

};

This lets us treat the PSRAM buffer as if it were a file. When we reach the end, just call reset() and start over. Simple and effective.

Parsing MJPEG: Finding Frame Boundaries

MJPEG is just a sequence of JPEG images concatenated together. Each JPEG image starts with the marker FF D8 (Start of Image) and ends with FF D9 (End of Image).

The parser’s job is to:

- Scan through the stream looking for

FF D8 - Copy bytes into a buffer until we find

FF D9 - Pass that buffer to the JPEG decoder

- Repeat for the next frame

Here’s the essence of the frame extraction logic:

bool readMjpegBuf() {

// Find Start of Image marker (FF D8)

while (buf_read > 0 && !found_FFD8) {

if (read_buf[i] == 0xFF && read_buf[i + 1] == 0xD8) {

found_FFD8 = true;

}

i++;

}

// Copy data until End of Image marker (FF D9)

while (buf_read > 0 && !found_FFD9) {

if (p[i] == 0xFF && p[i + 1] == 0xD9) {

found_FFD9 = true;

}

memcpy(mjpeg_buf + offset, p, i);

offset += i;

// Continue reading...

}

return found_FFD9; // Frame complete!

}

Once we have a complete frame, we hand it off to the JPEGDEC library which handles the decompression and renders directly to the display.

Gyro-Based Auto-Rotation: The Fun Part

The board has a QMI8658 IMU with both accelerometer and gyroscope. For orientation detection, we only need the accelerometer - specifically the Y-axis reading.

When the device is held normally (USB port on the right), gravity pulls down, giving us a positive Y acceleration. Rotate it sideways 180° (USB port on the left), and the Y reading becomes negative.

But there’s a problem: Sensors are noisy. If we just check the raw accelerometer value, the screen would flicker constantly as tiny vibrations cross the threshold.

Debouncing with Hysteresis

The solution is a two-part strategy:

1. Hysteresis - Create a “dead zone” around zero:

const float THRESHOLD = 0.5; // ±0.5g dead zone

if (accelY > THRESHOLD) {

desiredRotation = 1; // USB on right

} else if (accelY < -THRESHOLD) {

desiredRotation = 3; // USB on left (180° flip)

} else {

desiredRotation = currentRotation; // Stay put!

}

2. Debouncing - Require 1 second of stability before committing:

const unsigned long DEBOUNCE_MS = 1000;

if (desiredRotation != currentRotation) {

if (pendingRotation == desiredRotation) {

// Same desired rotation, check if enough time has passed

if (millis() - debounceStartTime >= DEBOUNCE_MS) {

currentRotation = desiredRotation; // Commit the change

}

} else {

// Different desired rotation, restart the timer

pendingRotation = desiredRotation;

debounceStartTime = millis();

}

}

This means you have to hold the device in the new orientation for a full second before it rotates. It sounds like a long time, but in practice it feels natural - you flip the device, and a moment later the screen updates. No jitter, no accidental rotations. Ah also since the video I played had some flowing liquid elements and a circle logo thing the other half, it rarely ever felt like it rotated, it just always felt as part of the video.

The OrientationManager Class

I packaged all this logic into an OrientationManager class:

class OrientationManager {

const float THRESHOLD = 0.5;

const unsigned long DEBOUNCE_MS = 1000;

const unsigned long POLL_INTERVAL_MS = 50; // 20Hz polling

uint8_t currentRotation;

uint8_t pendingRotation;

unsigned long debounceStartTime;

bool rotationJustChanged;

public:

void update() {

// Poll sensor at 20Hz

if (millis() - lastPollTime < POLL_INTERVAL_MS) return;

// Read accelerometer

IMU.update();

IMU.getAccel(&accelData);

// Apply hysteresis and debouncing logic

// ...

}

uint8_t getRotation() { return currentRotation; }

bool hasChanged() {

if (rotationJustChanged) {

rotationJustChanged = false; // One-shot flag

return true;

}

return false;

}

};

The hasChanged() method returns true exactly once when a rotation occurs, making it easy to react to orientation changes without continuously updating the display.

Button Controls

Pause and Power

The board has a BOOT button (GPIO 0) that we can repurpose for user interaction. Using the OneButton library, I set up two actions:

- Single click: Toggle pause/play

- Long press: Toggle power (blank screen + backlight off)

OneButton button(BTN_BOOT, true);

void onButtonClick() {

player.togglePause();

}

void onButtonLongPressStart() {

player.togglePower();

}

void setup() {

button.attachClick(onButtonClick);

button.attachLongPressStart(onButtonLongPressStart);

}

void loop() {

button.tick(); // Process button events

// ...

}

The power-off feature is especially useful for battery-powered scenarios. Long-press the button, and the screen goes blank with the backlight off, saving significant power while keeping the device technically running. (I do intent to expand this to actual deep sleep mode and auto timer based sleep as well for future iterations)

The Main Loop

Putting It All Together

After all that setup, the main loop is surprisingly simple:

void loop() {

// Check for orientation changes (20Hz polling internally)

orientationMgr.update();

// If orientation changed, update display rotation

if (orientationMgr.hasChanged()) {

player.setRotation(orientationMgr.getRotation());

}

// Handle button events

button.tick();

// Decode and display next frame (if not paused/powered off)

player.play();

}

That’s it. No complex state management, no threading, no interrupts. Just:

- Check the gyro

- Check the button

- Play the next frame

- Repeat

Uploading to Flash

The upload_to_flash.sh Script

Getting the MJPEG file onto the ESP32’s flash memory requires a few steps:

- Create a FAT filesystem image with the video file

- Flash that image to the FFat partition

I automated this with a bash script:

#!/bin/bash

# Find mkfatfs tool

MKFATFS=$(find ~/.arduino15/packages/esp32/tools/mkfatfs -name "mkfatfs" | head -1)

# Create filesystem image from data/ folder

# 10354688 bytes = ~9.87 MB (the size of the FFat partition defined in partition table)

$MKFATFS -c data -t fatfs -s 10354688 ffat.bin

# Find esptool

ESPTOOL=$(which esptool.py || find ~/.arduino15/packages/esp32/tools -name "esptool.py" | head -1)

# Flash to partition at offset 0x611000

# 0x611000 is the start address of the FFat partition (defined in partition table)

# --baud 460800 sets the upload speed (460800 bits/sec for faster flashing)

python3 $ESPTOOL --chip esp32s3 --port /dev/ttyUSB0 --baud 460800 \

write_flash 0x611000 ffat.bin

Just drop your output.mjpeg file in the data/ folder and run the script. The FFat partition mounts automatically on boot, and the video is ready to play.